Stockholm 2024

Last week, I visited Stockholm to join a good friend for some company visits and to attend the ‘Serial Acquirers’ conference organised by Redeye, an upstart Swedish broker. Some twenty companies attended, taking turns to present and host small group meetings with investors. You can access the presentations via Redeye’s site (link).

What is a Serial Acquirer, you ask? Put simply, it’s a business model which leverages the cash flow from a portfolio of companies to buy more companies. Many companies do M&A but Serial Acquirers make it their metier. This is possible thanks to three main factors. First, Serial Acquirers typically favour asset-light businesses that do not require much capital to grow, if they are growing at all (many are in mature industries). This creates a regular surplus of cash available for re-investment.

Second, Serial Acquirers are highly decentralised, with a lean headquarters staff delegating virtually all decisions to their operating companies except for capital allocation. This division of labour allows operators to flourish unhindered by bureaucracy while freeing capital allocators to focus on investing. Of course, the autonomy operators enjoy must be earned by delivering annual targets for growth and return on capital.

Finally, a Serial Acquirer must have an attractive pipeline of businesses to acquire. Europe seems like a rich hunting ground for niche industrial companies due to its industrial history, fragmented national markets and aversion to private equity (at least, relative to the US). Serial Acquirers typically prefer small deals that can be executed faster, present less risk to overall operations, and can be sourced by the operating companies themselves.

Past Performance…

There is sufficient interest in Serial Acquirers to host a dedicated conference because they have delivered exceptional returns to minority shareholders over a long period of time.

The table below compares ‘blue chip’ Swedish industrial Serial Acquirers Addtech, Lagercrantz, and Lifco to Constellation Software, a Canadian peer focused on Vertical Market Software (VMS) that has delivered best-in-class returns. It should be immediately apparent how profitable these companies are, how little they need to re-invest in organic growth and how much they re-invest in acquisitions.

Source: CapitalIQ

…IS A GUIDE

Having met with more than a dozen Serial Acquirers, I now have some insight into how my own clients feel when interviewing me. Most of my meetings were spent discussing their investment process and culture, all to divine a management team’s ability to reproduce past results. How did they do it? What’s their secret sauce?

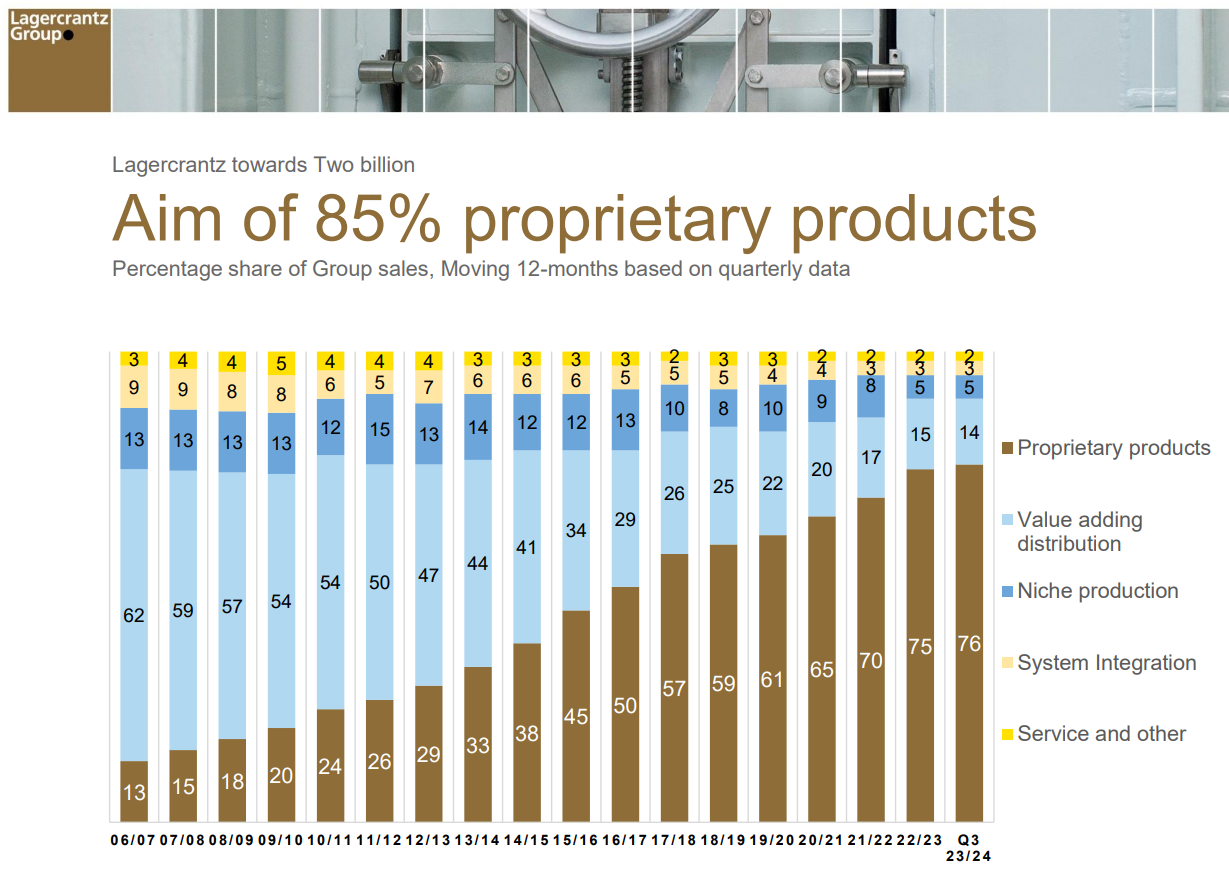

The second table below offers a clue: since 2010, Addtech, Lagercrantz and Lifco have all grown earnings per share faster than revenue per share. This was achieved by gradually migrating the focus of their operations and acquisitions to higher-margin activities and verticals.

Source: CapitalIQ

It sounds easy enough in hindsight, though I’m sure it was anything but. Lagercrantz was heavily exposed to the collapse in telecommunications capex following the Dotcom Bubble and was squeezed on both sides by consolidating suppliers and consolidating customers.

Lifco made a mental leap after listing to ramp up investment in Systems Solutions, a catch all to cover everything beyond Dental and Demolition, its original two verticals.

Unfortunately, having played the ‘margin expansion’ ace already, I suspect it will be harder for these three ‘blue chips’ to deliver outsize earnings growth again over the next decade. The bar is now commensurately higher.

paTIEnT CAPITAL

Dual-class share structures have enabled Addtech, Lagercrantz and Lifco’s long-term shareholders to retain control despite reducing their economic interest. This allows them to steward the culture of decentralisation, accountability and long-term thinking. We can see this in the degree to which the companies’ acquisitions fluctuate from year to year; they do not do deals just for the sake of it.

Source: CapitalIQ

On the other hand, Addtech, Lagercrantz and Lifco have not yet been as successful as Constellation in ramping up their investments to deploy an ever-greater amount of capital (measured as a percentage of revenue). This could be the lever with which they supercharge growth, though it will depend on the pipeline of deals available and their valuations. Relative to Constellation, the Swedish ‘blue chips’ also pay a greater percentage of gross profits as dividends, reducing the surplus cash available for investment.

Assets Matter

A discussion of the Serial Acquirers’ individual operating companies was largely absent from the conversation. This is partly due to the size and diversification of their portfolios. Addtech, for example, has over one hundred and fifty operating companies in its portfolio. As its CFO told me, to get bogged down in a single company’s performance would be to miss the forest for the trees. More important is for investors to select for themselves Serial Acquirers whose verticals are of interest (e.g. Road Safety, HVAC, VMS, lawncare etc.) or to find management they can trust to identify new, adjacent verticals for them.

Alternatively, led by Lifco, a growing number of Serial Acquirers have unconstrained mandates to find suitable businesses of any shape, anywhere. Lifco’s former CEO founded the (presently) unlisted company Röko, which appears to be the most eclectic. Its three most recent acquisitions were a cleaning detergents manufacturer in the Netherlands (link), an enterprise mobility solutions company in Australia (link) and a global ski instructor training company (link).

One conference organiser also hinted that investors care more about the theme than the details. According to them, for example, a popular Serial Acquirer, which recently issued discounted shares to a well-regarded American fund manager, stood out from the pack because its CEO wore running shoes to formal events, and its Deputy CEO published a book on mental models. I guess it’s no different from fund managers like me, who have to hustle for business however we can.

Nonetheless, the results of the past three years show that underlying assets matter. Industrial businesses are cyclical, especially those supplying the construction industry. Organic growth fluctuates and can go negative. There are also periods when deal flow dries up, as it has recently, because sellers’ expectations remain too high.

In the worst case, maintaining too narrow a focus in a small vertical can encourage managers to do deals they shouldn’t, as was the case with Addlife. Some verticals do not suit the Serial Acquirer model, either. Embracer’s rapid acquisition of a series of cash-flow-negative video game developers left it over-leveraged and over-extended when market conditions deteriorated.

As Do Liabilities

Eagle-eyed readers will by now recognise Berkshire Hathaway as one of the original Serial Acquirers. However, Berkshire stands virtually alone in its successful use of insurance to garner low-cost (usually negative-cost) insurance float to fund its investments. As I’ve written before, this form of leverage allows Buffett to earn a market return or better while taking less than market risk. It’s both a competitive advantage and a margin of safety.

In contrast, the Swedish Serial Acquirers I met primarily rely on two types of funding: short-term bank loans and vendor financing (e.g. earn-outs of one form or another). I was surprised that no one sought to take advantage of record-low interest rates three years ago by issuing long-term bonds, as Berkshire and Transdigm did so successfully in America.

I got the impression that adding value through the liability side of the balance sheet was seen as somewhat sordid. The reasons were kind of flimsy, to be honest. One CFO told me they would only rely on bank loans from Handelsbanken because of their controlling shareholder’s relationship with the bank. Others don’t want to take a view on interest rates, so they will only ever borrow short-term.

But doesn’t this “conservatism” create its own risks? What if the banking market freezes? Or if short-term interest rates spike?

The latter is exactly what happened in 2022-2023, leading to higher interest costs just as revenue and operating margins were under pressure too. Several of the companies I met are now deleveraging and “consolidating”. This has thrown sand into the gears of their acquisition machine and, in some cases, necessitated a potentially unhealthy degree of centralised decision-making to cut costs, restructure, and determine organic investment priorities.

Managing liabilities is one area that separates the men from the boys. Incentivising managers to use EBIT as a measure of profitability removes responsibility for managing interest costs. Only one company I met - truly, the best of the lot - insisted on using EBT precisely for this reason.

WHY SWEDEN?

I kept asking myself during the trip, why has the Serial Acquirer model worked so well in Sweden? There must be a connection to Swedish culture. Theirs appears to be a high-trust society that respects its institutions and customs; you can see this in the low crime rates and the way tax evasion is frowned upon. Yet Swedes appear to prize their autonomy and are unafraid to speak truth to power. My favourite example of Swedish common sense was the amount of jaywalking I saw in Stockholm. Contrast that with Japan, where I’ve seen people wait aeons on a deserted street for the light to turn green at a crosswalk.

(In fact, I couldn’t help but wonder: can Swedish decentralisation be applied to parenting? How can we give children autonomy while holding them accountable? This parental headquarters would love to delegate more.)

Then there are the role models. Bergman & Beving, the firm from which Addtech and Lagercrantz were spun out in 2001, is over a hundred years old. The eponymous founders began as import agents to supply Sweden’s industrialisation with foreign equipment. They had to be nimble to survive and later wished to imbue their colleagues with the same entrepreneurial spirit. In the 1970s, Dr. Jan Wallander referenced Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and other concepts as he radically decentralised Handelsbanken. He eliminated centralised budgeting and empowered every branch manager to run their own P&L and balance sheet. He is rightly seen as a Swedish business hero.

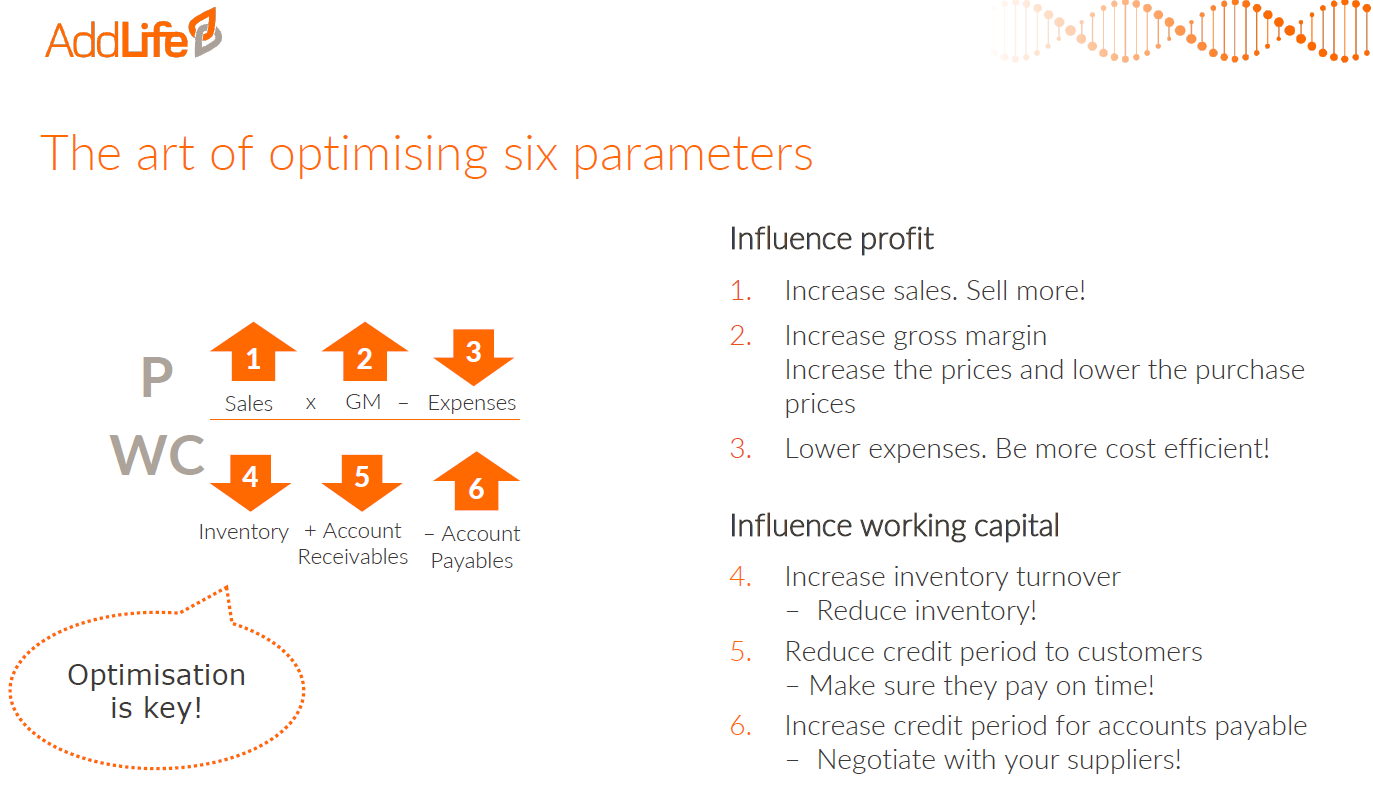

In “The Outsiders,” William Thorndike notes that high-performing CEOs tend to create a bespoke metric to act as their company's North Star. Bergman & Beving created the following simple but powerful ratio to measure the efficiency of a distribution company’s investment in working capital. In virtually every meeting, this formula was referenced for headquarters to efficiently and effectively manage its decentralised subsidiaries. A ratio of 45% or greater should produce more than ample cash flow to keep the machine turning.

Success begets success. As I learned at Redeye’s conference, a new generation of Swedish Serial Acquirers is now hoping to emulate the ‘blue chips’.

How About Asia?

Sadly, we don’t really have Serial Acquirers in Asia. Instead, we have conglomerates (Hong Kong and Southeast Asia), groups (mainland China), chaebol (South Korea) and trading companies (Japan). These emerged as the cash flow from a concession or legacy business was reinvested into a range of other businesses, either at the behest of policy-makers or to take advantage of the scarcity of capital from other channels. As analyst Michael Fritzell points out, related party loans from a bank controlled by a group can supercharge expansion by leveraging other people’s money (link).

For example, Lim Sioe Liong, the founder of the First Pacific group (listed in Hong Kong), was a Chinese rice trader in Indonesia who happened to supply a pro-independence guerrilla fighter named Suharto. When Suharto became President of Indonesia in the 1960s, he granted Lim a monopoly to process flour. Lim used this as the foundation to build one of the world’s largest instant noodle companies and then parlayed its profits into an empire of other businesses around Asia and the world, including, before the Asian Financial Crisis, one of Indonesia’s largest banks.

Unlike their Swedish counterparts, however, long-term returns for minority investors in Asian conglomerates have been poor because returns on capital have been low, weighed down by asset-heavy and cashflow-negative investments in real estate, banking, mining and infrastructure (or, arguably, Chinese Tech).

This explains why many Asian companies employ byzantine corporate structures, as founders seek to retain control even as they dilute themselves to fund their expansion or deleverage. Centralisation means acquisitions are larger, have a higher risk, and are often driven by a family member’s vanity as much as commercial logic. Ultimately, the lack of cash flow exacerbates the conflict of interest between controlling and minority shareholders, encouraging poor corporate governance.

Of course, there are exceptions and changes afoot. Just ask Warren Buffett about Mitsubishi, Itochu, and his other investments in Japan. Analyst Daye Deng penned an excellent write-up explaining the transformation of Japanese trading companies, which you can read here (link and link).

Wrapping it up

When clients invest with a fund manager like me, they do so at net asset value. When I invest in a Serial Acquirer’s portfolio of companies, however, I pay a premium. For the Swedish ‘blue chips’, that premium has increased materially since 2020.

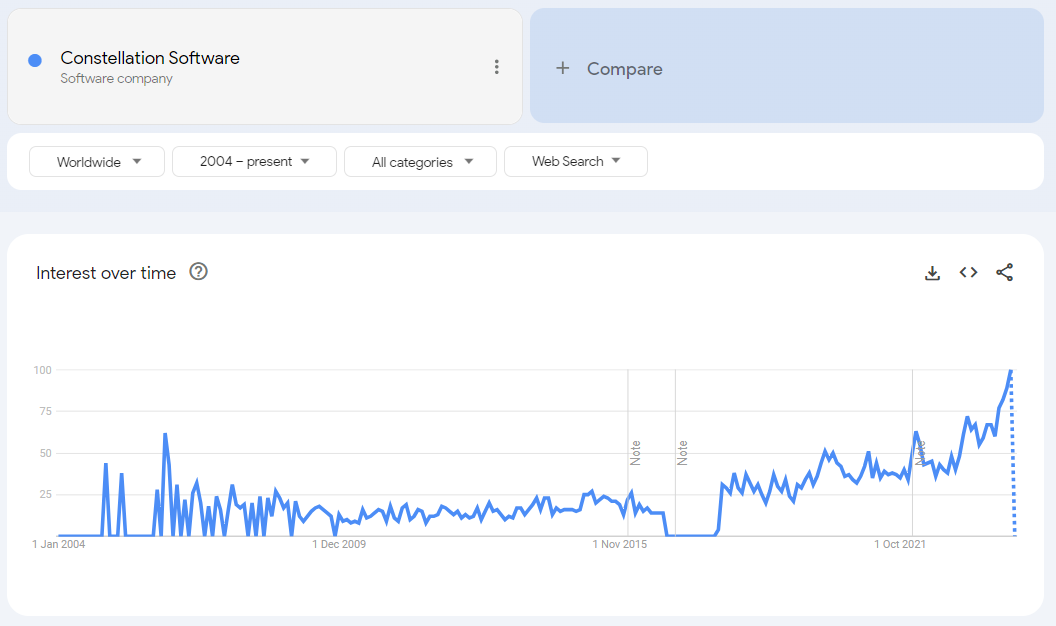

Is interest in Serial Acquirers at a peak? With all the talk about Constellation Software and the seemingly price-indifferent buying into the theme, it certainly feels like it. Google Trends concurs.

I’d love to tell you that the conference was terrible to discourage you from coming next year because it’s to my benefit for interest to wane and multiples to come down. But that would not be the truth. Redeye did a fantastic job organising the event, with much credit due to Eddie Palmgren, Christian Binder, Niklas Sävås, Jessica Bergwall and their colleagues.

Stockholm is a charming city to visit, too. If you go, you must stop by the Stockholm Public Library (pictured at the top), which rivals the Bodleian Library at Oxford. I stumbled across it entirely by accident and spent a happy few hours there reading former Handelsbanken CEO Jan Wallander’s book, “Decentralisation: Why And How To Make It Work”.

Further Reading:

Everything on Serial Acquirers by In Practise (link)

“They Made Us Rich”, an interview with Swedish author Ronald Fagerfjäll on Sweden’s entrepreneurial history (link)

Warren Buffett on why some businesses should not grow, the truth at the heart of the Serial Acquirer model (link)

Addtech’s twentieth-anniversary booklet, which introduces the history of Bergman & Beving (link)

Pinecone Assets, a nascent Serial Acquirer in Japan (link)

“Handelsbanken chief has no intention of changing ‘self-managed’ ethos” (link)